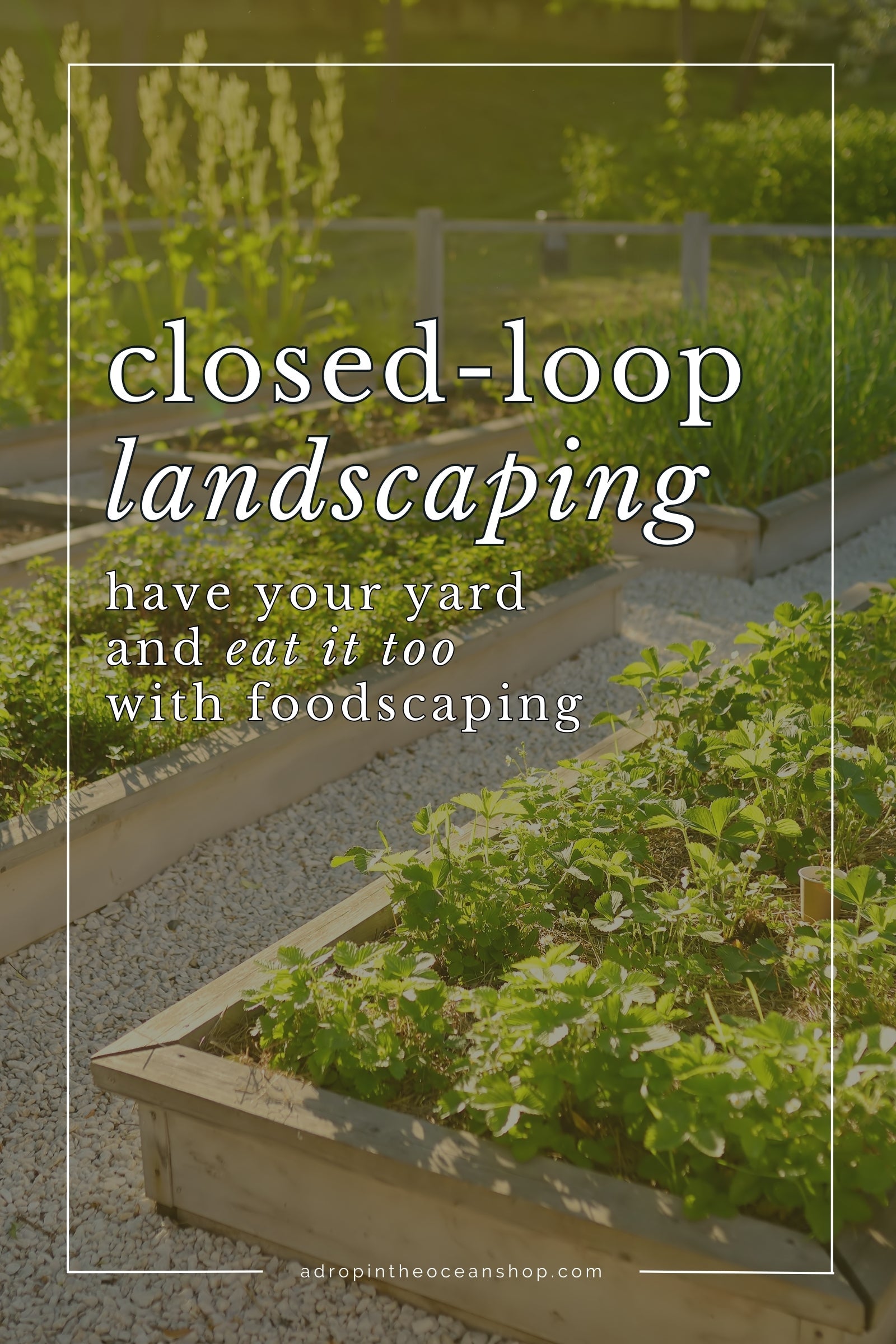

Closed-Loop Landscaping: Have Your Yard and Eat It Too with Foodscaping

This post first appeared in our weekly Make Waves Mondays email series on September 2, 2024.

I’m very excited to share this guest post with you because I know that as one of Krystina’s subscribers, you already share my deep commitment to connecting with land and other people. I’d like to continue the conversation we started with Robb’s guest post on the horrors of lawns by introducing you to edible landscapes, also called foodscapes. As we start looking toward fall, it’s a great time to plant because you don’t need to water (thanks rain) and the roots will get established over the winter and have a head start in the spring.

What is a Foodscape?

A foodscape is a landscape that emphasizes perennial, food-producing plants.

Foodscapes use both ecological science and landscape design principles to create spaces that are both beautiful and productive using fruit trees, berry bushes, vegetables, native plants, herbs, and flowers.

I recently watched the original Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory with my kids. There is a scene with a bright, candy garden about which Wonka says “everything you see is edible!” That’s how I view edible landscapes—abundant, vibrant, wonderlands that feed your family both physically and spiritually without tooth decay.

For example, in my front yard, we have a plum tree in the corner, close enough to the sidewalk to allow passers-by to harvest, blackberries growing on the hog-panel fence, kiwi-berry on the front-gate arbor, and currant bushes in front of the porch, all surrounded by native pollinator plants that are in full-swing right now like yarrow, aster, and goldenrod, plus a few traditional flowers like dahlias for fun.

Image courtesy of Custom Foodscaping

A foodscape can be as simple as potted herbs on an apartment balcony or as elaborate as a multi-acre homestead, or community food forest.

On my back patio, I have an old wash tub with a pot-size raspberry surrounded by calendula, marjoram, and oregano, with nasturtiums spilling over the sides. It’s adorable and my kids munch on berries while they play basketball.

Photo courtesy of Markee Ecological Garden Design

Why You Should Consider Foodscaping

In our current society, most of us are culturally disconnected from plants and land. We think food comes in plastic containers and have forgotten that food comes from the soil. So there’s something powerfully essential spiritually, politically, and biologically about growing your own food.

Whether you think in terms of food sovereignty or food miles, it’s empowering to learn to produce food, medicine, fiber, fuel, timber, and other essential goods and not rely on a flimsy global supply chain that depends on exploitation of people and land.

All of our ancestors, prior to global imperialist capitalism, had rituals and a world view supporting a mutually beneficial relationship with land, animals, and plants. Foodscaping isn’t new; it’s vintage.

It’s exciting to see increasing awareness and scholarship highlighting traditional encoded ecological knowledge and the ways in which humans have gardened for thousands of years. Like seeds buried under a parking lot, waiting for their moment to burst forth, this knowledge is making a comeback.

Even in the city, you can grow more food than you may think.

I live on a typical 5,000 square foot lot in Tacoma. Our house is 1,000 square feet and my family demanded that I leave some lawn for baseball so I’ve got about 2,500 square feet for food production. So far, I have 12 fruit and nut trees, and 14 berry bushes underplanted with strawberries, lingonberries, funky perennial vegetables like sea kale, tree collards, artichokes, rhubarb, and red veined sorrel, plus native lupine, yarrow, aster, goldenrod, and other tea and medicinal herbs, plus an annual raised bed zone to grow cabbage, kale, tomatoes, and other veggies.

Not everyone needs to do this much! Just replacing that sad rhododendron and scraggly hydrangea with blueberries will go a long way (and taste better).

Image courtesy of Custom Foodscaping

There are obviously huge issues of privilege here related to land access, destruction of traditional ecological knowledge and lifeways, and availability of time for working with land in a grinding capitalist economy.

I would not be growing any seaberries without the attempted genocide of indigenous peoples, racist real estate practices that supported me to purchase a home at the expense of black and brown families, and the economic position to spend time learning and tending my garden.

In true A Drop in the Ocean style, foodscapes can be closed-loop systems.

Foodscapes are carefully designed using a mix of functional plants that create nutrients for soil and retain water.

For example, plants in the legume family like beans, but also lupine, actually suck nitrogen out of the air and store it in the soil via a symbiotic relationship with their roots and special bacteria in a process known as nitrogen fixation.

Is your hair standing on end yet?

Other plants like yarrow and comfrey are dynamic nutrient accumulators, basically living bags of fertilizer. Plants that spread out and cover the ground like strawberry or clover form a living mulch that helps shade soil to keep it from drying out while also adding organic matter that will break-down and add nutrients to the soil.

If you have space for livestock (even a few chickens or rabbits), manure is one of the oldest methods for adding fertility to soil.

Butterflies and ladybugs love yarrow! Photo courtesy of Markee Ecological Garden Design

This is very different than industrialized agriculture that relies on huge amounts of inputs like synthetic fertilizer, herbicide, and patented seeds and produces tons of waste in the form of plastic irrigation lines, diverting water from rivers, and pollutant run-off.

Foodscapes foster community.

I notice that people slow down when they walk past my yard and wonder what the heck I did to the parking strip (native pollinator meadow!) or rest on the bench made from scrap wood we put along the sidewalk.

When you start growing food, you quickly begin living in a world of abundance which necessitates sharing.

I don’t just mean grandma’s zucchini. I started saving seeds for the first time last year and lost my mind when I saw the HUNDREDS of seeds I got from one plant. I do not need three hundred marigolds but maybe you need some so we can share.

The resilience enabled by growing your food also supports sharing because it reduces the sense of scarcity. When you know you have enough, you can give away the extra.

How to Start

I encourage you to start small with something you love.

If your favorite fruit is not a citrus, you can probably grow it here in Western Washington. You might take a sunny spot in your yard, sheet mulch it this summer, and plant an apple, plum, or fig tree, blueberries, and a few native plants this fall or next spring.

Gardening takes time, so don’t take on more than you can care for or the plants will suffer and you’ll get frustrated and throw in the towel. I see this all the time in the form of abandoned planting strip raised beds (pro-tip, put your raised bed by your kitchen so you’ll pass it throughout the day).

Once you get the hang of a small area, if you want to take on more, you can hire a professional like me through the Foodscaper Directory to design, install, and maintain a full-scale foodscape or create your own master plan for your site and implement the plan over time.

While I wish that foodscaping was the norm, we’re not there yet so it does take a bit of learning and sourcing plants from specialty nurseries since most mainstream nurseries don’t carry much selection of edible and native plants.

You can find lots of resources to help you on your journey on my website including books, online courses, plant and mulch suppliers, and much much more.

Get to know Anna!

Anna Markee is the owner of Markee Ecological Garden Design, an environmentally-focused landscape design, build, and stewardship firm located in Tacoma, WA. The company provides edible and ecological landscaping services. Every garden they create contributes to restoring soil health, growing food, supporting pollinator habitat, and restoring the water cycle. Anna previously spent 20 years working in public policy on issues ranging from affordable housing to land conservation. She lives with her wife and two young children who have beaten her to all the ripe raspberries this summer.

Related:

How sustainable are roses?

Is eating locally actually better for the planet?

Organic vs. Conventional - Does it really matter?

What do expiration dates actually mean?

Why You Shouldn't Rake Your Leaves This Fall

Your Lawn and the Ocean: How little green squares threaten the deep blue sea

Leave a comment